Whatever else happens along shipping’s journey towards net zero, one question cannot be ignored: where will the required carbon-neutral fuels be made? The large volumes of conventional hydrocarbon fuels currently used will have to be replaced by even larger volumes of e-fuels. The industry is forecast to grow by an estimated 67% by 2050. Since e-fuels have roughly half the energy of conventional fuels, twice as much will be needed to sail the same distance. Supplying those at scale and a cost that shipping can afford could change the geography of the global fuel supply.

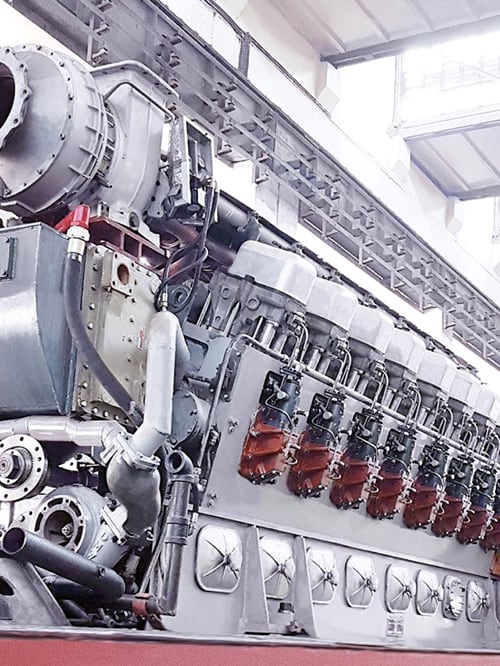

E-fuels must be manufactured using vast amounts of renewable energy to produce green hydrogen. Accelleron’s President of Medium and Low Speed, Christoph Rofka, says that 100-150 million tons a year of green hydrogen will be needed by 2050. Addressing the difficulties of producing it both economically and in large volumes, he says: “Scale helps to get the cost down.”

But where will large-scale plants be built, and how will their location affect shipping operations? These questions are at the heart of the second deadlock identified by Accelleron in its new report, summarized in seven words: concentrated fuel supply impacts global fleet flexibility.

Simply put, new fuel production sites will mean new bunkering arrangements. These will be largely restricted to ports in close proximity to new fuel hubs, or relying on a limited network of early market distribution. “That creates uncertainties,” Rofka says, because “there are many shipping companies who rely on having fuel available all over the world.”

Large scale keeps cost down

One company that already has big plans to produce e-fuels is InterContinental Energy (ICE), which is developing large hydrogen production plants in Australia and Oman. Its Head of Corporate Operations, Isabelle Ireland, was a panelist at Accelleron’s report launch at the 2025 London International Shipping Week.

Ireland says that the company specifically sought locations where they could find coastal deserts. The company’s Western Green Energy Hub (WGEH) in the Goldfields region of southwestern Australia, for example, has as much sun as southern Spain and, by night, as much wind as offshore Denmark; “a fantastic diurnal profile.”

Accelleron’s report says that this facility’s eventual size will be 30 times the size of Singapore, or one-tenth the landmass of the UK, or one-half the size of Switzerland. In essence, these are renewable energy hubs the size of small nations.

WGEH will generate 70GW of renewable electricity to produce 28 million tons of ammonia per year. Those statistics underscore the thesis behind the deadlock. As the report notes, “such scale can drive costs down, but it also concentrates supply in just a handful of locations.”

Container lines with predictable rotations can plan for this scenario, but bulk and tramp operators might not, the report says. It estimates that 70-80% of the global merchant fleet depends heavily on flexible routing. Paolo Tonon, Technical Director of Berge Bulk, asks: “Am I going to stop in Cape Town on my way from Brazil to China, just because it has all the infrastructure built for bunkering the fuels I need?”

That could add 10 days onto a 45-day voyage, Tonon says. But it won’t even be a possibility for many years. WGEH will take years to finish, with its first phase coming on stream in the early 2030s. It has its own port to draw maritime customers, but will serve other industries too. ICE’s maritime interest was piqued by IMO’s decarbonization program, Ireland says, speaking before regulatory progress towards that goal was put on hold in October.

Massive demand for e-fuels

These e-fuels still will not be cheap, the report predicts, saying that green ammonia even from vast hydrogen hubs will be about $650 per ton in today’s money, compared with $500 for conventional fuel.

Accelleron identifies four factors that influence its views on how fuel supply impacts global fleet flexibility. It first looks at the economics of energy density, noting that the leading e-fuels – methanol and ammonia – contain only about half the energy density of conventional marine fuels.

Professor Lynn Loo, CEO of the Singapore-based Global Centre for Maritime Decarbonization, notes: “When we compare fuels, [we] compare tonnage because that’s how we buy fuels. But really, for ships’ use, you have to compare based on how much energy they use.”

Even if ammonia’s costs were reduced to $800 per ton by the 2030s, through the International Maritime Organization’s Net Zero Framework, adjusting for energy density would push the effective cost of usable energy closer to $1,600. Even Ireland’s projected $650 cost would mean $1,300 on an energy-adjusted basis, the report says.

Could a smaller-scale, modular e-fuel model offer optionality?

In Asia Pacific, Envision Energy offers a practical counterpoint to the mega-hub model. Its modular e-ammonia facility at Chifeng in Inner Mongolia entered commercial operation last year, producing around 300,000 tons annually, with expansion planned in stages rather than in million-ton leaps. Instead of waiting for shipping demand to consolidate, the project aggregates early offtake across power generation, chemicals, and industrial hydrogen users, allowing production to begin while global maritime carbon pricing is delayed.

This cross-sector approach changes the sequencing of the transition. Land-based demand provides the revenue stability needed to bring e-fuel capacity online early, while shipping remains a future customer rather than a prerequisite. As global maritime demand strengthens, driven by the International Maritime Organization’s Net Zero Framework, these modular plants can scale incrementally and connect to bunkering networks without having stranded capital waiting for regulation to arrive first.

Book-and-claim mechanisms reinforce this model. By separating the environmental attributes of carbon-neutral fuels from their physical delivery, shipping companies can begin participating in the e-fuel market even where direct access is limited.

Together, modular production and book-and-claim offer a way to break one of shipping’s central deadlocks: achieving economies of scale that drives carbon-neutral fuel production into a small number of concentrated locations, while global fleet flexibility depends on widespread, geographically distributed bunkering access that does not yet exist.

A combination of large-scale hubs for long-term cost reduction, modular cross-sector production for early volumes, and credible book-and-claim systems may therefore provide a more resilient pathway through the transition. It does not eliminate the need for global regulation, but it reduces the risk of delay by allowing shipping to join the energy transition earlier, gradually, and with greater operational flexibility.

Find out more about how to resolve this and the four other deadlocks slowing the maritime energy transition in the full report here.